Today, we often hear that 'time' goes by too fast. This impression - not to a certain extent unreasonable - is basically due to the massive presence in the population of new communication technologies (computers, internet, electronic mail, cell phones, videoconferences, etc.), which began to become popular in the 1990s.

Undoubtedly, the current pace of personal relationships, business, banking transactions, and exchanges of messages contrasts sharply with that dictated by everyday life in societies a few decades ago. This new, constantly changing society has its origins in the way the world was seen thousands of years ago by thinkers in Egypt, Greece, Mesopotamia, India, China, etc.

These men and women were philosophers of nature, and there, are the foundations of mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, areas of knowledge that gained enormous theoretical and practical impetus with the Renaissance in Europe and what many historians call - even though without consensus on this interpretation though - 'Scientific Revolution', from the 16th century.

And right there, very briefly, is the long journey that science has undergone to be made as it is today. This path has been paved with elements considered inherent (and necessary) in making this culture: observation, questioning, experimentation (including in the form of thoughts, idealizations), data generation, logical interpretation, analysis and rational thinking... But also errors, misunderstandings, prejudices, doses of metaphysics, frauds ... as good articles and books on the history of science show us. At certain points in history, it has been impossible to trace a clear dividing line between science and metaphysics, as the early stages of development show, for instance, chemistry and alchemy, as well as astrology and astronomy.

From an anachronistic point of view (and certainly partial), the 'Scientific Revolution' is almost synonymous with the European continent. However, we must remember that other populations, in other regions of the world, had their ways of seeing the cosmos and terrestrial phenomena. This is the case, for example, of the Brazilian natives, who knew the technique of making fire; they made sophisticated bows and arrows; they produced perfect hydrofoil canoes; they built shelters for up to hundreds of residents; they knew how to orient themselves by the stars and by the sun; they recognized seasons of the year; perceived (and compensated in fishing) the refraction suffered by the light that passes from the water to the atmosphere; opened wide roads and large squares between settlements...

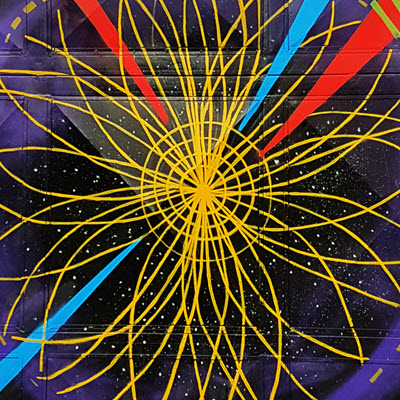

It is yet to be understood how the culture of these populations helped to erect the high building, housing the knowledge accumulated from the Renaissance to the present, in which science has become - as stated by the British historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012 ) “the most important form of culture”; with its discoveries ranging from nanoscopic dimensions (from billionths of a meter), such as subatomic particles that flow from powerful particle accelerators, to the world of bodies with gigantic masses (stars, black holes, galaxies, etc.) and speed close to that of light (300,000 km / s), through technologies linked to the manipulation of genes and the social and economic transformations that have come to the forefront of advances in communications.

“The word science comes from Latin; it means 'knowledge.' It is difficult for me to believe that anyone can be against knowledge. I think science works as a delicate balance between two seemingly contradictory impulses. One is the capacity for synthesis, which creates hypotheses; and the other, the analytical, skeptical capacity for scrutiny. It is only the mixture between the two, the generation of creative hypotheses and the careful rejection of those that do not correspond to the facts that allow science and any human activity, I believe, to advance."

- Carl Sagan -