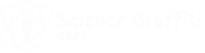

The very small; the very large; what we can see; the invisible; the elementary particles that make up matter; the interaction between them; the light ... In short, the magic of nature and its facets still unknown. This area of the ‘Science Graffiti Wall’ reminds us of the technological advances that have moved and still move humanity. What else will come out? The complex (for some, useless) art of futurology always plays tricks on us, for in every unexplored corner of nature there is something lurking, a discovery that, when revealed, changes the course of humanity.

The LHC - which can be understood as the most powerful microscope constructed by human ingenuity - investigates the ultimate constitution of matter and the fundamental forces of nature. It was in this wonderful machine with four gigantic detectors scattered along its nearly 30-km-long ring that the Higgs boson was discovered, a particle that confers mass ownership to all other entities in the vast subatomic zoo of matter. In its more than 60 years of operation, CERN has made an invaluable contribution to broadening the knowledge behind a simple question: 'what are things made of?’ A question that began with the atomists, about 2,500 years.

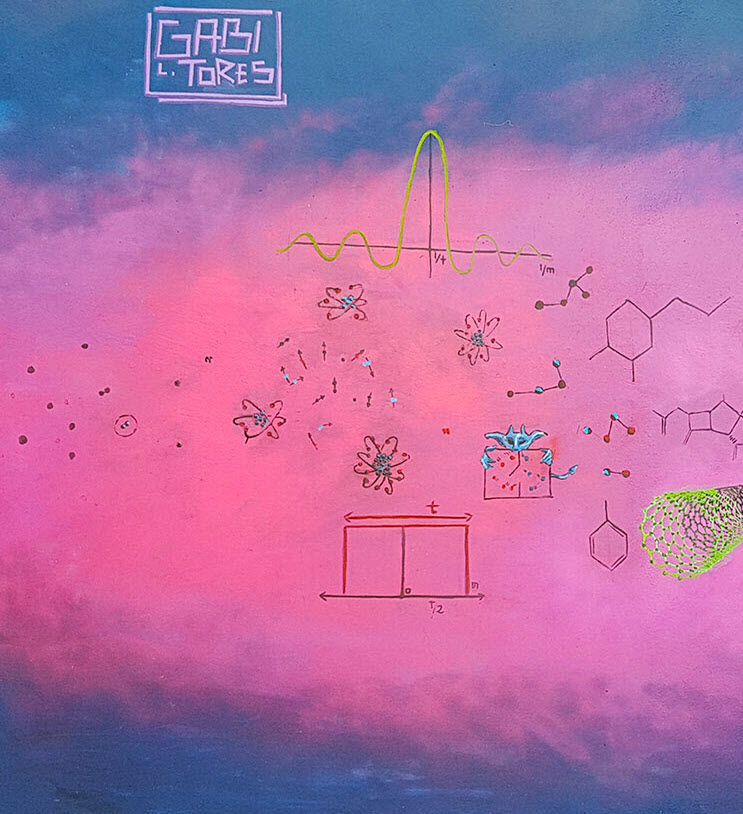

Technology is the most visible facet of science - the latter made, most of the time, in a disinterested way, without any immediate compromise with the 'what is it for?’ Technology is, to a large extent, the application of basic science. However, in modern times, it is increasingly difficult to draw a clear boundary between scientific research and technological research, given the interdisciplinary of the areas. And, not rarely, technological advances may precede basic results in science, and propel the search for more fundamental explanations of phenomena.

In this part of the ‘Science Graffiti Wall’, some technological applications have been chosen to illustrate the transformation of knowledge into devices and tools that underlie the well-being and economic progress of nations. X-rays, electric engines, gears, internet, airplanes, rockets, etc. The highlights are the Hubble telescope which for decades has been searching the cosmos; the Voyager I spacecraft, which, after visiting Jupiter and Saturn, ventured into interstellar space, beyond the boundaries of the Solar System; the international space station, a wonderful scientific enterprise of peaceful international cooperation. And, of course, a tribute to the most complex structure known: the brain, with its hemispheres represented here as electronic (hardware) and digital (software) devices. Right in the center of this organ, a reference to quantum computing, which promises ultra-high speed processing. This section of the panel is a reference to the human being as an actor responsible for the conscious use of the applications of science for the construction of a fair and more equal society.

In this part of the panel, the scientific-technological adventure continues: cosmic rays, ultra-energetic atomic nuclei whose spatial origin is only now beginning to be unraveled; the great observatories in world collaborations, a new way of doing science in the line of 'unity is strength' with its origins in the period just after the end of World War II; radio telescope systems, for analysis of astronomical signals and vision of the cosmos from different forms of light (microwave, X-ray, gamma ray, etc.).

The understanding of matter in its most intimate dimensions and the endless cosmos, with its fauna of bodies and phenomena, is the borderline that the human being has imposed on himself and which has been broadened since the beginning of philosophical-scientific thought in antiquity. It is precisely this disinterested pursuit, without immediate practical purposes, that is the basis of great technological advances over the centuries. Hence the importance of remembering that, at the heart of every technological wonder that permeates our daily lives (computers, internet, cell phones, tomographs, airplanes, cars, medicines, etc.) is a good dose of basic science.